DeepBook - “The Backbone of Sui DeFi Liquidity”

In our piece on perpetual decentralised exchanges (perp DEXs), we made the case that the majority of order book–based DEXs, such as dYdX and Hyperliquid, use an off-chain order book with on-chain settlement as a means to improve transaction fees and reduce latency at the order book stage. Maintaining an order book entirely on-chain requires every order placement, cancellation, or modification to be recorded on the blockchain, incurring gas fees and introducing latency limited by block confirmation times.

In our piece on perpetual decentralised exchanges (perp DEXs), we made the case that the majority of order book–based DEXs, such as dYdX and Hyperliquid, use an off-chain order book with on-chain settlement as a means to improve transaction fees and reduce latency at the order book stage. Maintaining an order book entirely on-chain requires every order placement, cancellation, or modification to be recorded on the blockchain, incurring gas fees and introducing latency limited by block confirmation times.

DeepBookV3 is a decentralised central limit order book (CLOB) protocol that operates using an on-chain order book. It benefits from lower fees and faster block verification times, inherited from the Sui blockchain on which it is built. DeepBook is developed by Mysten Labs, the same team that created the Sui blockchain.

As an open-source protocol, DeepBook positions itself as a Sui-native, permissionless, foundational liquidity layer that SUI built dApps can integrate into their platforms. This means applications can access DeepBook’s order-book functionality without needing to build their own matching engines. Each individual protocol can route its orders to DeepBook, which combines all of them into a single, shared pool of liquidity.

Deepbook advertises high throughput, low latency at ~390ms settlement times, and trading with minimal slippage. The Sui blockchain offers identical block finality times as low as ~390 milliseconds, fees averaging $0.002 to $0.01 USD (depending on transaction complexity), and parallel execution made possible through its custom consensus mechanism, Mysticeti-C.

Mysticeti-C, which we covered in our previous report, offers a low-latency DAG-style consensus mechanism and parallel execution. This allows DeepBook to scale high throughput which is necessary in an order book system where multiple traders will be placing trades and interacting with the protocol simultaneously. Additionally, the low ~390 ms settlement times offered by Sui are essential for Deepbook’s on-chain CLOB.

Overall, DeepBook’s ability to offer an on-chain order book while remaining competitive as a DEX is made possible by the cheaper fees and quicker block times offered by SUI’s core architecture.

Every element of Deepbook’s protocol is implemented on chain through the use of interlinking smart-contract modules built with Move, the native language of Sui, and made feasible by Sui's object model which differentiates between shared and owned objects.

In Sui everything that exists on-chain, from tokens to smart contracts, is represented as an object. Each object carries its own data and ownership information. Some objects are owned, meaning they belong to a single user and can only be modified by that user’s transactions. For example, a user’s wallet balance or an NFT would each be owned objects and only the holder of that object’s private key can change or transfer it. Other objects are shared, meaning they can be accessed or updated by multiple users at once. These include decentralised exchanges, on-chain order books, liquidity pools, and governance smart contracts where many participants interact with the same shared object.

The distinction between owned and shared objects determines which path a transaction takes through Sui’s Mysticeti consensus. Owned-object transactions use the fast path (Mysticeti-FPC) for rapid, parallel execution since they affect only one user’s state, whereas shared-object transactions must go through the Mysticeti-C path to reach full consensus. In particular the normal path will order transactions before finalising because if multiple users interact with the same shared object simultaneously, their actions may conflict or depend on one another. For example, in Deepbook multiple users can simultaneously interact with the exchange at once so transactions must be sequenced before execution so that prices, order matching, and state updates happen in the correct order.

Each market, e.g. SUI/DEEP, SUI/ USDC, is stored as a shared object on-chain and named a “Pool”. Everything about that market, its orders, state and settlement, lives inside this Pool object. Going back to the Mysticeti C consensus mechanism, shared objects allow many users to interact with the same “pool” simultaneously.

Each pool consists of three distinct on-chain components: Book, State, and Vault, which each manage a different component of the order lifecycle. The (order) Book manages the list of open orders, including bids and asks and matches trades. The State records user accounts, historical data such as trading volumes and fees and key governance parameters; while the Vault is responsible for on-chain settlement.

The (Order) Book

The bid and asks on the order book are stored as data structures on-chain which are responsible for storing, matching, modifying, and removing orders. When an order is submitted, the system generates an object that encapsulates all trade parameters, such as price, quantity, and order type. To reduce latency and optimise the protocol at the millisecond level, the data is optimised by using efficient ordering of the parameters. This reduces matching time and additionally storage fees which reduces computational power and therefore total gas fees, which is calculated by the storage and computational requirements of a trade.

When an order transaction is submitted, Sui validators collectively check its validity, vote on it via the Mysticeti C consensus mechanism and once consensus is reached, the transaction is “certified” and executed. Validators are also collectively responsible for ordering the transactions so the ledger remains accurate and up to date. Some smaller logic such as wallet UI and user interface can be off-chain but the core Deepbook protocol is on-chain.

How does DeepBook avoid / penalise wash trading?

One definition of wash trading is the buying and selling of an asset by the same trader in order to artificially inflate trade volumes, or take advantage of some discrepancy between the fees paid and fees received for making and taking an order.

On DeepBook, traders have an incentive to wash trade due to the role of the protocol’s native token, DEEP. The DEEP token is used in three verticals:

- Providing volume-based taker fees

- Providing maker incentives

- Staking

DeepBook operates in a series of epochs, which each last for 24 hours. Every epoch has a variety of different pools — i.e., markets such as SUI/ USDC, or some other tradeable pair. Prior to every epoch, traders can decide whether they would like to stake any DEEP tokens and if so, to which pools they would like to stake to.

Any trader who is a price taker (executes buy or sell orders at the best available current price) but does not stake DEEP tokens will pay a flat taker fee per transaction for every trade in that pool for that epoch. That fee is paid in DEEP tokens. For non-stablecoin pools, the taker fee is between 5bps and 10bps. However, if a price taker’s staking of DEEP tokens for a particular pool exceeds a specific threshold and the volume of their trades in that pool also exceed the same threshold, every extra trade they place as a taker becomes eligible for a halved taker fee (e.g, 5bps). For stablecoin swap pools, the taker fee is between 0.5bps and 1bps.

Makers are traders who submit a desired price level at which they will buy an asset and/ or sell an asset. These traders pay a flat maker fee (between 2bps and 5bps for non-stablecoin pools) regardless of their staked DEEP or trade volume. However, they are eligible for a maker incentive if they stake a minimum amount of DEEP tokens — at the end of an epoch, they are rebated on some of the total maker and trader fees generated in the pool. It is this rebate that can provide an incentive to engage in wash trading.

So firstly, how does DeepBook compute the incentive paid to a maker at the end of an epoch for a particular pool? Take a particular maker called Maker A. Maker A’s incentive to provide liquidity is a function of a number of different variables, including:

- Fees generated by the traded volume from maker A

- Fees generated by the traded volume provided from non-DEEP staking makers as well as DEEP-staking makers

- Traded liquidity provided by all other makers in the pool

These variables underpin the equation that governs the incentive paid to maker A. One key aspect of the equation is that an individual maker’s incentive to provide liquidity is counter cyclical. As aggregate liquidity in the pool increases, maker A earns less rewards for providing liquidity — once liquidity in the pool hits a certain threshold, A’s marginal incentive drops to 0 (but never negative). The threshold at which liquidity in the pool is considered abundant such that maker incentives become zero is calculated in an automated manner: it is the median of total liquidity distributed by staking and non-staking makers in the past 28 epochs (28 days).

When liquidity in the pool dries out, i.e., when there are limited makers submitting buy and sell prices, maker A will receive a higher incentive for providing liquidity. His incentive is at its maximum when there is no other liquidity provided by any other makers in the pool. Additionally, the more makers in the pool that do not stake DEEP tokens, the more maker A benefits — this is because the incentives that would have been paid to those makers is shared among those that did stake DEEP.

Secondly, what does this mean for wash trading? On a holistic basis, the fees generated from takers and makers will always be less than or equal to the incentives paid out to makers. This ensures that on aggregate every pool on DeepBook remains solvent. However, there is no perfect defence mechanism against wash trading. In a wash trade, a trader pays both the maker and the taker fee (they post their own order as a maker, then fill that order as a taker). This means they are eligible for a maker incentive at the end of the epoch.

One such scenario where wash trading is profitable is when there are two liquidity providers (makers) in a pool. One is maker A, who stakes DEEP tokens and the other is maker B who does not stake his DEEP tokens. If both maker’s liquidity gets traded on, i.e., maker A posts a wash trade order and fills it himself, and maker B posts a genuine order that gets filled by another taker, maker A’s reward is a function of the fee generated from his liquidity as well as the foregone fees of maker B’s liquidity (since he did not stake any DEEP). In such a case, wash trading is profitable because maker A breaks even on the fees he paid on his wash trade, but is also rebated the fees that would have been given to maker B had he staked a sufficient number of DEEP tokens. Note, in this scenario we also assume that the aggregate liquidity in the pool is far from abundant, therefore maker incentives are higher (counter cyclical).

According to the DeepBook protocol whitepaper, the fact that there is an incentive to wash trade is “the unfortunate and accepted side effect of trying to make incentives as generous and effective as possible during low liquidity periods”. Ultimately, there is no protocol specific factor that prevents a trader from engaging in wash trading. One mechanism adopted by the protocol to slightly reduce the likelihood of wash trading however is to burn any excess fees of DEEP tokens generated in the pool beyond those rebated back to makers. This ensures there is no other ex-ante mechanism to recoup incentives. For example, if residual fees were deposited in some community treasury program and paid back to makers in some later epoch, it could increase the inclination to wash trade — to avoid this, excess fees are permanently burned.

Another common malicious activity is spoofing. This is when a maker posts an order with no intention of delivering, aiming to remove the order as price gets closer to it. The formula underpinning maker incentives looks at the traded liquidity provided by makers, not just the liquidity quoted. We also know that maker and taker fees are paid when orders are filled. Hence, there is no explicit penalty, or protocol-specific incentive to post fake orders on the book and then remove them. Nor is there any protocol specific factor that guards against engaging in spoofing, similar to wash trading. Spoofing can however have “extra-protocol benefits to the trader”, i.e., to take advantage of price dislocations that stem from spoof orders.

Does DeepBook Penalise Toxic Takers?

DeepBook defines toxic takers as buyers who intentionally exploit moving prices by filling orders at a market maker's price that has become “stale” before the market maker is able to cancel or update their outdated quotes. For example in the SUI/USDC market, if the price of SUI is rallying, market makers may still be displaying older, cheaper quotes, and a toxic taker may be able to buy at this outdated cheaper level. Toxic takers do not include a lucky buyer who happens to purchase before the price rises; instead, it refers specifically to the intentional taking of stale orders in the order book, at the expense of market makers, in an arbitrage-driven behavior labeled as “toxic flow”.

To understand how toxic takers facilitate this trade, we refer back to the Sui blockchain’s consensus mechanism, where gas-fee tips give transactions priority and otherwise a first-come-first-served ordering applies. This allows takers to pay to have their orders processed first in the hope that their buy order will be executed before a market maker can cancel or update order requests. Additionally, takers can minimise latency through high-frequency technology and direct server routes.

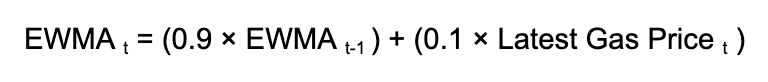

To mitigate the opportunities for toxic flow that this system introduces, DeepBook tracks the average gas fee per market, with each pool maintaining its own independent average. It then applies an additional 0.1% taker-penalty fee to traders who submit unusually high gas prices, defined as values that exceed a threshold statistically above the pool’s exponentially weighted moving average (EWMA) gas price. This average gas price is calculated using a “10% weight on new data, 90% on history”. In the EWMA formula, “new data” means the latest gas-price observation, and “historical data” refers to the previous EWMA value. With this logic, all past gas-price observations have an exponentially decreasing weight on the latest average gas price:

The mechanism is designed specifically to target takers who exploit the gas-fee prioritisation system to front-run and outrank other orders. It relies on the assumption that the only reason a trader would want to pay unusually high gas fees, statistically above the average of transaction fees for that pool, is that they want their transaction executed first because they stand to benefit from hitting a stale market-maker quote.

Mathematically, Deepbook calculates the penalty threshold as a Z-Score of 3 or above the average of the pool’s own gas fees which can be understood in more detail here. In theory this model aims to target the takers with the highest gas fees that land in the top ~0.3% of observations. In practice, a gap remains between ‘above-average’ gas fees which can still gain prioritisation and the penalty threshold of a Z-score above 3, within which opportunistic takers can operate without incurring a penalty. For a toxic taker, this becomes a trade-off between increasing the likelihood of hitting the market maker’s stale (but attractive) quote and avoiding the additional 0.1% taker penalty fee.

MEV

Transactions on blockchains introduces Maximal Extractable Value, (“MEV”) which refers to the additional profit that a block producer or validator can extract by reordering, inserting, or censoring transactions during block construction.

MEV depends on the ability of a validator to control the ordering or inclusion of transactions within a block. This control enables them to manipulate the sequence of transactions to generate profit, for instance by inserting their own transaction before another (front-running), after another (back-running), or by selectively excluding or reordering transactions. MEV is most well known on Ethereum, where the consensus mechanism allows a randomly chosen single validator to control the construction and proposal of a block, while other validators will only verify the validity of transactions (valid signatures, correct state transitions, gas limits, ect.), but not choose the transaction ordering.

On Sui, before any Deepbook transaction enters the Mysticeti consensus, each validator in the active committee independently performs a set of pre-validation checks to ensure the transaction’s integrity, verifying that the user’s signature is valid, the referenced objects actually exist and that there is sufficient gas to cover execution.

Once the transaction is approved, it enters the consensus mechanism. Validators must reach consensus on the order of transactions collectively, meaning that no single validator has the exclusive power to reorder transactions to gain Maximal Extractable Value (MEV). Instead, all validators propose blocks simultaneously at the start of each round. During the proposal phase (round one), every validator creates and broadcasts a block containing new transactions, referencing blocks from earlier rounds to form the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) structure. In the support phase (round two), validators propose new blocks that link to at least 2f + 1 of the round-one blocks, effectively voting in favour of committing them. Finally, in the certify phase (round three), validators again propose blocks that reference the supporters from round two, and once a round-one block receives both sufficient support and certification from the validator network, it is finalised. This leaderless, multi-proposer design ensures that block ordering emerges collectively from validator references rather than from a single leader. Because of this, individual validators can’t selectively reorder or delay transactions for MEV without reaching consensus on their proposal with the wider network.

Mysticeti-C uses a DAG-based (Directed Acyclic Graph) structure in which validators continuously propose blocks that reference each other’s previous blocks, collectively determining transaction order without relying on a single leader. The protocol is largely leaderless—each validator participates equally in proposing and supporting blocks—though temporary leader blocks are used as a fail-safe to finalise undecided rounds. Consensus and finality are achieved when a proposed block receives support from at least 2f + 1 validators in one round and certification from another 2f + 1 in the next, ensuring that ordering results from the network’s collective agreement rather than any single validator’s preference. This design minimises the potential for individual validators to reorder or delay transactions for MEV purposes.

Although traditional MEV is not possible by an individual validator in SUI, “network-race MEV” or “user MEV” is. This refers to situations where arbitrageurs submit the same SUI-based trades, but due to the validator ordering of transactions, only one can capture the profit. Arbitrage opportunities can exist when the price of an asset varies between different platforms and protocols.

Arbitrage bots who spot the opportunity will submit the same trade to DeepBook, but MEV arises because shared objects must be ordered and the SUI network can only process one state update at a time. Therefore, the arbitrage opportunity is dependent on the validaotr’s ordering of transactions. This is not decided by validator manipulation but instead depends on several technical and network-level factors.

The most fundamental is network propagation latency, how quickly a transaction reaches the validator set. Under Mysticeti, transactions are finalised once they’ve been referenced by enough validator nodes in the DAG. A trader whose transaction propagates faster, due to better connectivity or proximity to validators, has a higher chance of being finalised first. Geographic and network proximity matters since Sui’s validators are distributed globally and Mysticeti relies on fast message propagation. Traders who use low-latency servers near major validator clusters or maintain direct peer connections to validators gain an advantage, similar to co-location in traditional finance but on a decentralised scale.

Another factor is the transaction broadcast strategy. Some traders optimize how they distribute transactions by sending them to multiple SUI validator nodes simultaneously, using private relays or direct connections. These methods increase the likelihood that at least one copy is received and referenced early in the DAG, improving the odds of being finalised first.

Gas price can play a minor role with arbitrage bots submitting multiple transaction copies with slightly different gas parameters. Mysticeti doesn’t allow validators to reorder based on gas price like Ethereum. However, if validator mempools become congested, transactions involving shared objects on Sui are given execution priority based on gas price. This is an indirect form of MEV, applicable only when the Sui network is busy, meaning transactions with higher gas fees are more likely to be processed first by validators during consensus.